- Type: R&D project

- Client: Self-initiated by Studio Hartzema & FRESH

- Partner: Vereniging Deltametropool

- Core team: ir. Henk Hartzema, Dipl. -Ing., ir. Aikaterina Myserli

- Status: 2019 – Ongoing

Project Holland is a self-initiated project managed by the newly established R&D department in Studio Hartzema. The key aim is to confront our future, embrace change through design and leave behind conservative tendencies that prioritise economic profit over sustainable development. The project started with collecting data about the current level of pollution, environmental instability and sea-level rise consequences and went on delivering useful infographics, diagrams and disruptive visuals that cultivate a positive attitude towards change. The final goal is to engage our audience -which exceeds our circle of professional architects, planners and developers-, and help them become partakers in the unfolding of a new, sustainable future.

Part I: Project Holland and The Flooded Atlas

Before we can talk about the redesign of the Netherlands, it is good to determine where the future of the country lies. The most obvious choice is the trade-off between the Netherlands below and above sea level. The largest part of our population and a large part of GNP is invested in parts of the country whose existence is relatively new. The day that the rivers no longer flow into the North Sea but come to a halt halfway through our country comes closer.

Part II: Scaling-up decision making

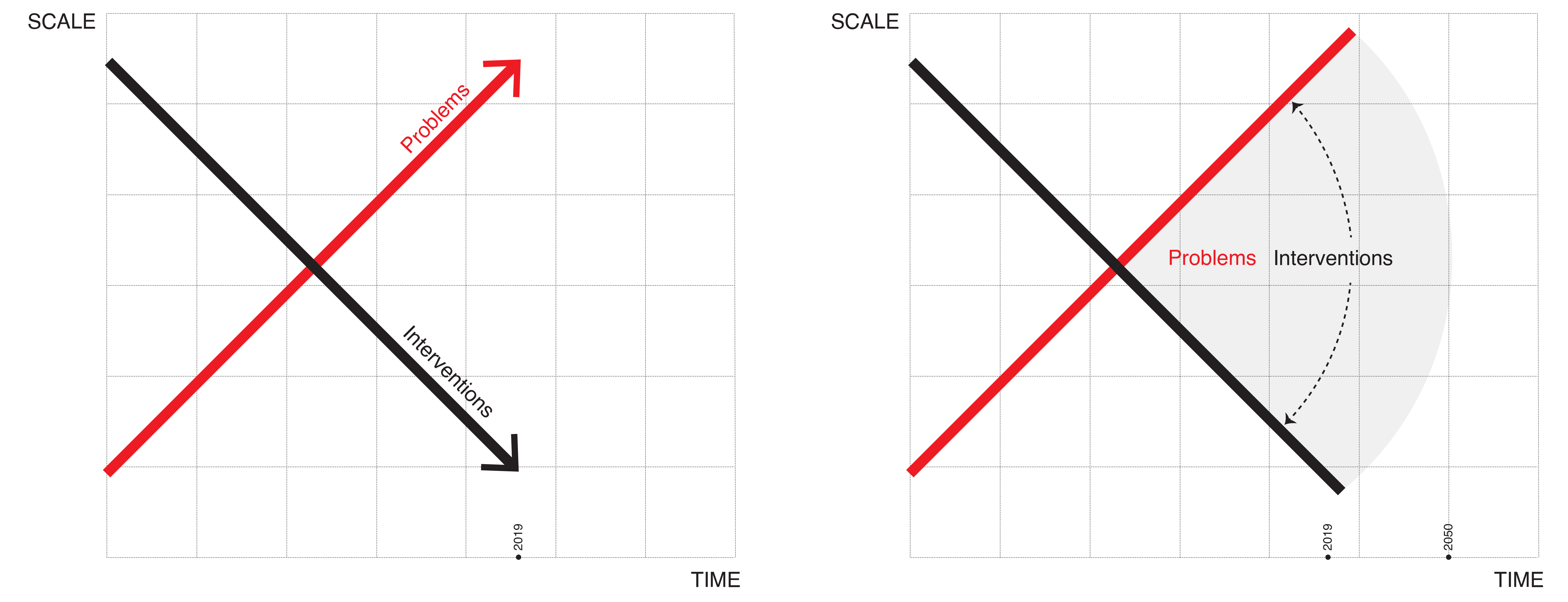

Although contemporary spatial issues become larger, decision-making does not move along. Despite the fact that fragmented versions of smart cities, wind farms and solar parks are generously offered by various design agencies, municipalities, energy companies and government institutions worldwide, the gap between high-level decision-making and processes of self-organization on a local scale is greater than ever.

Dutch planning tradition has its origins in the autonomy of the individual spatial components. Nevertheless, many centuries of careful planning and engineering have resulted in a certain minimum of centralized planning that is necessary for the survival of the Randstad and the Netherlands as a whole. The Randstad has yet to experience this kind of paradigm shift. Divided into different administrative entities and governance boundaries, it is often suffering from miscoordination between different sectors and asks for more integrated strategies between the various stakeholders. When superimposing the historical Beemster grid (934m x 934m) on the unbuilt territory of the Randstad, it becomes clear that the space available could evolve either into a sharing entity between different cities or into a field of conflict between them.

Similarly, the global upscaling of socio-metabolic processes will also require cooperation and planning on a high level. Without a united vision and a direction towards singular metabolism -to the extent that this is possible- we will find ourselves unable to cope with climate change. And this will inevitably have serious boomerang effects on our current socio-economic backbone. Project Holland sheds light on large-scale interconnected interventions that will make us partakers in the unfolding of transition and will bring change on our threshold.

Part III: The Netherlands is getting bigger

Large-scale appropriation and conversion of the neutral space of Randstad into vast forests, solar meadows, wind farms or types of biomass crops will lay the foundation for designing energy transition, awareness and, most importantly, helping society embrace radical changes.